You may recall from my posts in Paris that there was nothing I enjoy more than a good art exhibit: it could be anything from medieval makings of Christ to postmodern contemporary works, street art or studio art, Manet or Monet – either way, I’ll take it. There is something so different about artwork – the way one image can capture so many different political, social, and aesthetic perspectives fascinates me. Coming home from Paris, I opted for a class on art history that has satisfied my craving for artistic culture, and has opened my eyes to the endless possibilities of what our imaginations and hands can do when we have no truly fulfilling way to express ourselves. Each two hour class is chalk full of new, insightful information about not just the visual characteristics of works – the perpetually red and blue representations of the Madonna, or the use of a dog in various works as a symbol of eroticism – but the way that they convey political issues and social attitudes. Impressionism, what we now accept as an aesthetically pleasing style that often decorates our walls, coffee mugs, and notecards, came out of many changing attitudes in 19th century France, including the Haussmanization of Paris: the newly transformed city became a place to see and be seen, and thus the focus on first impressions and momentary judgements. All this means to say that art is important to not just culture, but to the advancement of our society as a whole. So, with a more educated and critical eye, I’ll take you back to some of my favorite works, using my newfound art history knowledge to offer a more insightful perspective.

Edouard Manet, Olympia, 1863

Olympia is, without a doubt, my favorite painting. She adorns my desk, a little reminder of my days standing in front of her at the Musée d’Orsay after dates with my French fling. Olympia was a prostitute/escort in the days of Manet (“Olympia” was a common name for prostitutes at the time – someone in my art history class offered the contemporary equivalent of “Candy” as an example), and Manet’s rendering of her is one of rebellion and change. Her un-idealized body rejects the norm for previous works: she is every bit a true woman, but doesn’t look like the women of more critically appraised works from the École des Beaux Arts. She isn’t tall and curvy, with flowing hair and long legs. She is a realistic interpretation of a woman – and Manet did this on purpose. Olympia’s gaze is also significant: most paintings of woman prior to this had them gazing off in the distance, unable to stare the viewer in the eye. Olympia, however, looks right at you. She confronts you, forces your gaze upon her and challenges you with the confidence and coolness of her eyes. Her servant offers her a bouquet of flowers, presumably from a, ahem, suitor. If you look at the background, Manet cuts it in half using a wall, and the line that bisects the painting leads your gaze directly to the placement of her hand and the symbolism of her gesture. The eroticism and overt meaning of her hand placement was another finger at the École, who would approve of such a gesture if only it were a married woman addressing her husband.

Oh wait…someone already painted that? You mean Manet was a copycat? Hold up…

This work from 1505 – the Venus of Urbino by Titian – is an almost direct match to Manet’s later representation of Olympia. Visually, they are practically a direct match: even the center line bisecting the work has the same effect of leading your gaze to the woman’s genitalia. Even their names echo a mythological understanding – Venus and Olympia are both powerful Greek references – and the color palette, general setup, and subject are shockingly similar. So what did Manet do differently? Well for one, Titian’s work is quite obviously a woman about to be married, and the viewer is intended to be her new husband. This means that her open eroticism is acceptable. Manet, on the other hand, challenges the social norm by blatantly presenting a prostitute. Even the womens’ gazes suggest different attitudes: Venus offers a flirtatious, intimate gaze, and the dog at her feet – a recognizable symbol of eroticism – suggests that the viewer is someone familiar, as it is curled up and undisturbed. Manet’s version gives us a black cat in place of the dog, which suggests dark femininity as opposed to deep familiarity. Olympia, unlike her doppelganger three centuries prior, is blunt in her sexuality.

I don’t know what it is that draws me so fiercely to Olympia, but there is something about her perpetually challenging gaze, her starkly realistic features, and her cool demeanor that hits home for me. If ever you go to Paris, make this number one on your bucket list: standing in front of Manet’s masterpiece is an unforgettably surreal feeling.

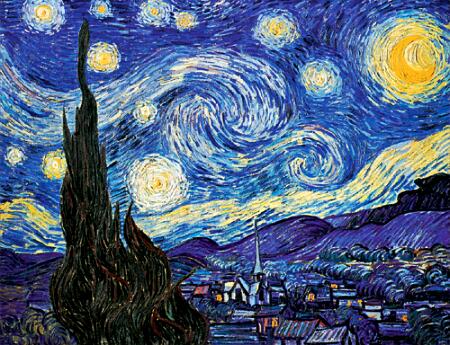

Van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889

Okay, I know, perhaps a piece that is almost over appreciated. Van Gogh was a master of his craft: before beginning his work as a painter, Van Gogh studied contemporary art in Paris, examining the works of his fellow artists. From Georges Seurat (he made those cool pointillism paintings) he took the science of color contrast, and from Paul Cézanne he took the uniform style of brush strokes. Combining these ideas, Van Gogh was able to create works with intense visual vibrancy that almost explode off of the canvas. The Starry Night is a prime example of this:

Boom! Wow. This painting is incredible. First of all, I must correct a common misconception which was recently corrected for me, as well. Van Gogh is known for being kind of crazy, and while it’s true that he was in and out of mental institutions, he only ever painted in “moments of lucidity” (words from my professor). That is to say, he painted when he was sane. He was also deeply spiritual, and I don’t think anyone can contest that this painting seems to singlehandedly confirm the existence of a higher power. Van Gogh’s most famous work is a masterpiece of color contrast theory as well, and the careful, deliberate selections of color and their layering on top of each other allow the shades to melt together to expose something much grander than just a canvas with paint. The view represented in the painting was the actual view from Van Gogh’s room in an asylum, and the cypress tree on the left that was outside his window becomes an explosion upwards and towards the heavens. The most prominent building in the landscape, the church, gives a strong religious context and again directs the gaze upwards to the heavens. And of course, the massive swirl of color in the sky – it’s almost like a visual translation of Van Gogh’s search for something higher, something more than his own existence. But what really blew my mind when I learned about this painting……is this:

This is the Japanese artist Hokusai’s work The Great Wave at Kanagawa. The fluidity and intensity of the wave is directly translated into the heavens of Van Gogh’s painting. As well as studying contemporary French art, Van Gogh was a zealous student of Japanese art, and studied alternative ways to represent spatial configurations. These methods are evident in many of his works, but perhaps no more obvious than in the similarities between Hokusai’s great wave and his own starry night. Lucky for me, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City is the home of this breathtaking masterpiece, so I will be taking a trip to see it as soon as I possibly can this summer.

Gustave Courbet, L’origine du monde, 1866/The Stone Breakers, 1849

Judge me if you will, but I love this painting. I saw it in the Musée d’Orsay, and had to get over my giggles. I know it probably seems like my art choices are full of naked women, but how badass is this painting? I think I liked its shock factor, as well as its subtle humor in the title – “The Origin of the World”. Courbet was great. He was a pre-Impressionist painter who succeeded in portraying the harsher side of French rural life, but was also commissioned for such works as this (an “erotic” work was ordered by a wealthy Turkish diplomat). Courbet pushed the envelope, challenging what was acceptable artwork, like Manet had with Olympia.

Above is Courbet’s The Stone Breakers, a work that was selected for the Salon (big, awesome art exhibit that only admitted the “best” French artwork). You can see the difference between Courbet’s commentary on French peasants, and his commissioned work that used overt eroticism to challenge cultural norms. The Stone Breakers is a blatant criticism of French society at the time, depicting a young man and an old one executing the tedious and seemingly ridiculous task of breaking up stones (there was a purpose, I swear, but even then it seemed dumb). As you can see, the background is dark and mountainous, overcoming the subjects and seeming to provide no escape whatsoever except for a tiny sliver of blue sky. From left to right, you see the progression of young to old, which implies that the life of a poor peasant is unescapable for life. Both of these works are favorites, but I have to say that I prefer the openness, blatant eroticism, and subtle humor of his later work – it’s just kind of awesome.

Fun fact: the shoes being worn by the older man in The Stone Breakers are called sabots. They were a wooden shoe worn by French peasants. When workers wanted to disrupt work, they would throw their sabots into the machinery they were working with. This is the origin of the word sabotage. Who knew!?

I was going to do more works (there are so many), but seeing how I’ve rambled, I’ll stop here and pick up in another post. I hope you’ve enjoyed these examinations – these works are all ones that I’ve formed a connection with on some level, particularly Olympia. With each passing moment I get substantially more excited at the prospect of visiting the MoMa and Guggenheim this summer in NYC….I can’t wait!

For some more of my favorite works, check out the Musée d’Orsay’s impressive collection:

http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/collections/discovery.html